Can a new economic engine revive vacant offices?

Two powerful trends are gripping the US economy: vacant office buildings and advanced making technologies. Savvy developers are unlocking a new urban economy by combining the two

For the last century, most cars were designed around a very specific engine. It governed the vehicle’s internal mechanics, aesthetic design, and the policies, like gas tax, that surround the automobile industry.

Similarly, the city was also designed around a specific kind of engine—this one, economic. Since the 1980s, the American downtown was revved by office space: big companies, knowledge workers, and the constellation of services that support them. This engine defined how we build and understand cities, from transportation to building design to the tax revenues that define municipal budgets.

That engine has been sputtering for a while, but during Covid-19 the last piston fired. In the aftermath of the pandemic, businesses aren’t leasing office space at the same rate – or scale – as before. Professional norms and return-to-work policies are stabilising around 50% of pre-pandemic levels.

Grinding to a halt

Across the US, cities are struggling with a glut of no-longer-desirable downtown office space, especially class B and C buildings. In Portland Oregon, vacancy rates are close to 40% – and that estimate doesn’t count spaces that are leased but vacant, with contracts soon to expire.

Without the engine of a bustling real estate market, urban economies are slowly grinding to a halt. Portland’s 20 largest office spaces had a combined market value of US $3 billion in 2019—today, the value has dropped to US $1.3 billion. The city saw a ~1% assessed value growth in 2024, the lowest on record for Portland since the late 1990s. In the Urban Land Institute’s national survey of ‘development attractiveness,’ Portland is just about zero.

As an architect and urbanist, I refuse to give up on cities; their vibrant sidewalks, heritage buildings, and agglomeration effects. So what are we going to do with all of this vacant architecture? What kind of economic engine will drive cities along the winding road of the next few decades? If the familiar value proposition of downtowns—offices for office workers—is gone, we need to find a new one.

The new value proposition

Office to housing conversion is a popular idea in cities like Portland. While this concept works in theory, sitting at the convergence of the vacant real estate dilemma and the housing crisis, many office buildings are simply unfit for residential conversion.

Deep floor plates and limited plumbing are just two of the many factors that make office to housing conversions economically and architecturally unfeasible. The only project that’s even close to happening in Portland received significant subsidies from the local economic development agency.

If we are truly creative and strategic, the new value proposition for downtown buildings will solve parallel problems, like housing, but it will also fit comfortably into the building stock, and it will be more than just economically viable: it will actually drive a new urban economy. What is it? Hold that question.

Outsourcing innovation

Since the early 1980s, companies competed by effectively off-shoring production. They converted their value proposition from making things to designing things that are made somewhere else. Nike is a great example – every pair is made by a ‘Tier 1′ factory that sells finished shoes to the footwear brand you’re familiar with. Apple is the same way; designed in Cupertino, made in China.

Whether it’s shoes or iPhones, the design process is cumbersome, with slow and expensive iterations between design teams and production teams working on opposite sides of the globe. It can take 24 months for a shoe to go from a concept to being laced up. For a long time this global setup worked, primarily because of the eye-wateringly low cost of labour in countries like Bangladesh, Indonesia, China, and Vietnam, and the economies of scale that arise when making immense quantities of product (not to mention advertising: if you can make your customer demand your product in two years, the delay isn’t a problem).

But something started to happen as supply chains globalised: the US outsourced its capacity for innovation. Today, the Tier 1 suppliers that make everything from shoes to electronics in Asia are far more sophisticated than any in the US. Over the past 50 years they didn’t just make products, they also made massive leaps forward with the technologies and processes for making products.

That includes a flourishing of advanced manufacturing technology, such as 3D printing, dimensional knitting, robotics, and computer vision. These technologies have matured beyond their initial use case (prototyping) to find a role in more efficiently creating all manner of end user products that look and function unlike anything familiar.

Towards advanced manufacturing

The advantages of advanced manufacturing go far beyond aesthetics. These technologies are sustainable, fast, and relatively small. They are inherently dynamic. Even if they raise the price of a single unit, companies save because they aren’t obligated to produce massive quantities. A 3D printer can create one component just as easily as another (often both at the same time), while a conventional factory requires days or weeks to set up for a single product. That means brands can read and react to the market. Production is pulled by demand, rather than pushed by supply minimums.

The trend toward advanced manufacturing has a long history, but it has accelerated dramatically over the past five years, after the pandemic shattered our intricate global production system. Factories shut down unpredictably, throwing supply chains into chaos. Brands paused orders, and the suppliers that had structured their competitiveness around a single wage rate, tariff regime, or workforce geography went bankrupt. During the first half of 2025, daily tariff announcements continue to cause whiplash across industries.

A new form of competitive advantage is coming into focus: localising at least some production processes close to home, and leaning into the inherent strengths of advanced manufacturing technologies. Brands can achieve efficiencies while recapturing the innovation capacity that comes from making. They can iterate quickly to meet the demands of the market, and produce only enough to meet demand. They can make sustainably, and offer supply chain transparency to an increasingly socially conscious consumer.

Not everything can or should be made in any single country. The domestically produced iPhone is a fiction. But a ‘Made in USA’ 3D printed basketball shoe is a slam dunk.

Test driving a new model

At the convergence of vacant real estate and advanced manufacturing lies significant opportunity for urban renewal.

And you can see it in downtown Portland, today. Made in Old Town is an innovation campus for the design and production of footwear and apparel. For anyone familiar with the Old Town neighbourhood, it is an unexpected location for an innovation campus.

This is the neighbourhood that put Portland in the national spotlight, winning it a reputation as a wasteland of boarded up windows and drug abuse. But it is also where you can find the city’s most beautiful heritage buildings selling for less than 30% of their 2019 asking price. Old Town is a bellwether for the American downtown. And its historic brick walls and old growth timber columns are now humming with advanced manufacturing technologies.

Phase 1 of the Made in Old Town development encompasses over 110,000 square feet across three buildings, bringing a full supply chain to a two-block radius. Overseas, in places like Wenzhou in, China, León, in Mexico, and Ho Chi Minh City, in Vietnam, supply chains thrive on proximity. Dense networks of suppliers, brands, manufacturers, and logistics providers make it easy to test, iterate, and rapidly scale production. They collaborate and compete at a rapid pace, using readily available infrastructures, and drawing on deep pools of talent.

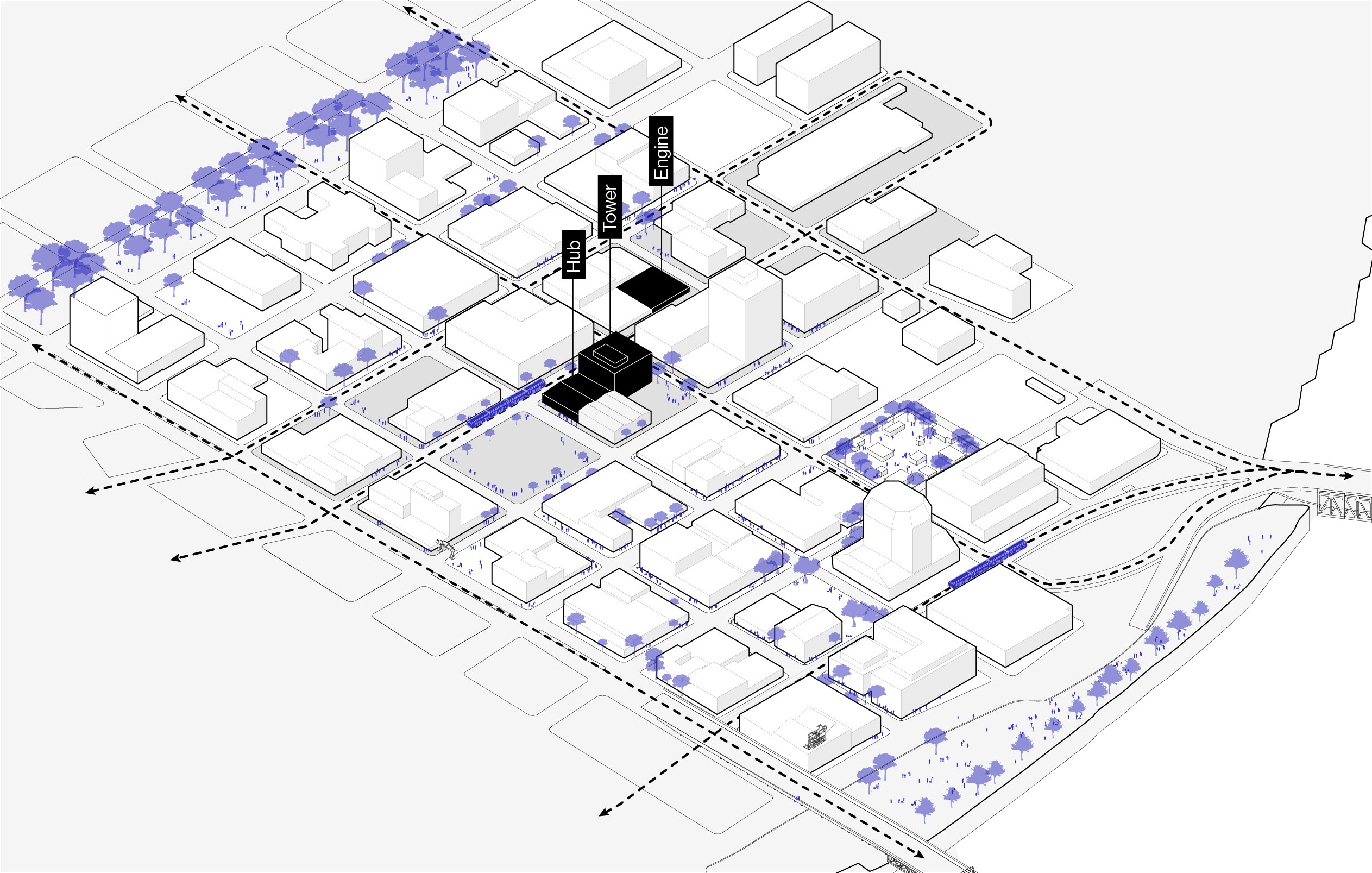

Diagram of the Made in Old Town development, courtesy of Field States

At Made in Old Town, the proximity effect is even stronger, because production happens right next to the design and innovation process driven by brands, independent creatives, researchers, entrepreneurs, and students. The toughest problems, from sustainability to performance to cultural zeitgeist, are best solved when design and production are co-located.

The campus is becoming a central node for the 500 plus+ brands that are already in Oregon, and an attractor for global talent, offering culture, networking, and workforce training. It centres on the nation’s largest open materials library for footwear and apparel, and advanced manufacturing equipment capable of creating fully functional shoes and garments using both conventional and cutting edge technology.

Lab space in Made in Old Town, courtesy of West of West Architecture and Design

Small-run, high-mix production will happen alongside retail and take-back systems for consumer interaction, sustainable recycling, and urban-integrated logistics. These features are surrounded by housing and urban amenities, rolling out in Phase 2 of the development. Made in Old Town will be a place for urban life and wellbeing, not just production.

The project is being designed by West of West Architecture and Design and Field States, alongside other collaborators.

More than real estate

Localised urban production is about economic development as much as it is about real estate development or industry transformation. Made in Old Town is bringing US $125 million to a neighbourhood that has seen systematic disinvestment, and opening up viable, future-proof career paths on all rungs of the ladder. The first phase of the project alone, costing US $15 million, is projected to have an economic impact over US $90 million, bringing 380 jobs to Old Town.

‘The future is in making fewer, better, more sustainable products’

Will this neighbourhood ever compete with Chendai Town in China’s Fujian province? Absolutely not. That city alone churns out over a billion pairs of shoes annually. But if you believe that the future is in making fewer, better, more sustainable products by streamlining the innovation and production process, Old Town is where you will place your bet.

The past and future of production

Portland isn’t alone. Almost every city in the US has a history of making, from Rochester’s cameras to jewellery in Providence; from furniture in Grand Rapids to bicycles in Dayton. These industries stir pride, recalling a time when heritage brands like Kodak and Schwinn were forming and craft mattered.

In each of these cities, robust domestic production shifted to knowledge work over the course of the 20th century. And as knowledge work shifted remote in the early 2020s, every one of these cities hollowed out, leaving behind a glut of office space.

The next chapter of American cities will require us to reimagine what ‘work space’ really means: buildings with innovation and production, perfectly suited to regionally-significant industries.

The automobile transition, from gasoline to electric, taught us that a new engine will have dramatic implications throughout the vehicle, from drive train to console, as well as policy, pricing, and user experience.

‘Light, clean, innovation-driven production will demand that we reimagine buildings…’

It will be no different for cities. The new engine of light, clean, innovation-driven production will demand that we reimagine buildings and the amenities they offer, how they are priced and leased, how they are activated, and the policies that surround them. The savvy workplace leader will navigate this transition, leveraging the opportunities of innovation and production.

Just like automobiles, we need cities that are high-powered, clean, and resilient. An engine that offers a great user experience without compromising performance. This will have dramatic implications for buildings and the amenities they offer, pricing and membership, activation and experience, the urban technology layer, and economic resilience.

With a new economic engine, American cities are poised to accelerate, rather than stalling.

This article is part one of a two-part essay. The second piece is a shorter, visually rich study of the building design, workplace programs, and interior architecture strategies for innovation-driven downtown production.

Matthew Claudel is a keynote speaker at the upcoming WORKTECH25 San Francisco conference. He is the founder of Field States, an urban design and real estate strategy firm that generates new value through place-based transformation. He has a PhD in Advanced Urbanism from MIT, and has co-authored two influential books: The City of Tomorrow and Open Source Architecture. Matthew co-founded MIT's successful designX accelerator program. As Strategic Design Lead for healthcare company Curative, he scaled their vaccination program from a strategic roadmap to one million doses in five months. Matthew worked with the Boston Mayor's Office of New Urban Mechanics and was a juror for the Canadian Federal Government’s $50M Smart City Challenge.

Matthew Claudel is a keynote speaker at the upcoming WORKTECH25 San Francisco conference. He is the founder of Field States, an urban design and real estate strategy firm that generates new value through place-based transformation. He has a PhD in Advanced Urbanism from MIT, and has co-authored two influential books: The City of Tomorrow and Open Source Architecture. Matthew co-founded MIT's successful designX accelerator program. As Strategic Design Lead for healthcare company Curative, he scaled their vaccination program from a strategic roadmap to one million doses in five months. Matthew worked with the Boston Mayor's Office of New Urban Mechanics and was a juror for the Canadian Federal Government’s $50M Smart City Challenge.